La recente decisione del Tribunale dell’Unione Europea del 21 gennaio 2026 nel caso T-43/25 ha confermato il precedente orientamento secondo cui nella valutazione circa la somiglianza tra marchi, i segni devono essere confrontati nella forma in cui godono di protezione, vale a dire così come sono stati registrati o come figurano nella domanda di registrazione, mentre il loro uso effettivo o potenziale in un’altra forma è irrilevante ai fini del loro confronto.

Il Tribunale UE ha rigettato il ricorso proposto dalla celebre azienda di abbigliamento sportivo Puma SE con cui quest’ultima aveva chiesto l’annullamento di una precedente decisione del Board of Appeal dell’EUIPO. Con quest’ultima era stata rigettata l’opposizione dell’azienda tedesca – fondata sul rischio di confusione ex art. 8(1)(b), Regolamento UE 2017/1001 – nei confronti della domanda di registrazione, da parte di una società cinese, di un marchio figurativo consistente in una striscia curva e un triangolo irregolare posti all’interno di un rettangolo nero per la Classe 25.

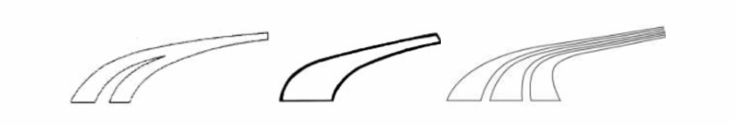

In particolare l’opposizione di Puma si basava su alcuni propri marchi figurativi anteriori consistenti in una o più strisce bianche curve che risalgono verso destra, tutti registrati per la Classe 25. Come gli appassionati di running certamente sapranno, si tratta di segni, noti come “Formstrip”, che Puma impiega da decenni sulla tomaia di moltissimi dei propri modelli.

Il Tribunale UE ha confermato le considerazioni svolte dal Board of Appeal sulle notevoli differenze tra i segni oggetto del giudizio, in specie riguardo la diversa configurazione geometrica degli stessi, soffermandosi anche sull’eccezione sollevata da Puma circa il fatto che il segno contestato non fosse altro che una versione capovolta dei propri segni e che, per i prodotti della classe 25, è comune utilizzare segni in posizione ruotata o speculare a causa della natura del capo d’abbigliamento e del movimento di chi lo indossa (ma – si potrebbe aggiungere – anche solo per fini estetici, essendo numerosi i casi di scarpe e abbigliamento sui quali i celebri marchi sono stati apposti dai rispettivi titolari con “angolazioni” diverse da quella con cui sono impiegati abitualmente). Ciò comporterebbe secondo la ricorrente il rischio che il segno contestato possa essere utilizzato in posizione ruotata, rendendolo simile ai marchi anteriori.

Nella decisione viene quindi ricordato come, secondo un costante orientamento, nel valutare se siano identici o simili, i segni devono essere confrontati nella forma in cui godono di protezione, vale a dire come sono stati registrati o come appaiono nella domanda di registrazione, mentre l’uso effettivo o potenziale dei marchi registrati in un’altra forma è irrilevante ai fini del confronto dei segni. Infatti, precisa il Tribunale UE, l’orientamento dei segni, come indicato nella domanda di registrazione, può avere un impatto sulla portata della loro protezione e, di conseguenza, al fine di evitare qualsiasi incertezza e dubbio, il confronto tra i segni può essere effettuato solo sulla base delle forme e dell’orientamento in cui tali segni sono registrati o richiesti (par. 34 e 35).

In applicazione di tale principio il Tribunale UE, in un caso sempre relativo ad un marchio figurativo applicato alla tomaia di alcune sneakers, aveva già stabilito che il raffronto tra i segni come in concreto potrebbero apparire su delle calzature sportive è irrilevante (Caso T‑581/17, Asics c. EUIPO, par. 43). Il Tribunale UE ha dunque disatteso anche l’ulteriore osservazione proposta dalla ricorrente circa il fatto che una delle differenze rilevate dal Board of Appeal tra il segno contestato e i segni “Formstrip” di Puma consisterebbe nel rettangolo nero che fa da sfondo al primo e che tale rettangolo, se posto su prodotti di colore nero, sostanzialmente sparirebbe. Ebbene, proprio perché irrilevante l’utilizzo concreto del segno, il meramente ipotetico uso del segno contestato su scarpe di colore nero non può giustificare l’opposizione da parte di Puma.

Infine, come anche viene evidenziato nella decisione, bisogna comunque tenere a mente che il titolare della registrazione ha un diverso strumento giuridico a tutela dei propri diritti sul segno. Le doglianze del titolare di marchio anteriore circa eventuali utilizzi del segno altrui in forme diverse da quella presente nella domanda di registrazione possono infatti essere fatte valere in sede di contraffazione (par. 70 e la decisione ivi citata nel Caso T‑76/13, Compagnie des montres Longines, Francillon c. OHIM, par. 58).

for transport services in class 39.

for transport services in class 39.